A good film score can take a bad movie and make it watchable. A great score can take a good film and make it memorable. When you have an iconic film score, the kind of thing you find yourself humming weeks later, the film it was meant to enhance had better be amazing. Sometimes, there is a full orchestral sweep, bringing big emotions that wash up against your ears. Other times, it can be as simple as the piano from “Halloween.” The right hand plays the repeating melody and the left hand hits the same note to build tension. The night is dark. The fear builds. You’re hooked. And that is before the rest of the musicians begin. There is also the near-angelic sound of “Tubular Bells” by Mike Oldfield that serves as the theme to “The Exorcist.” That thing makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up every time I hear it begin. A score can do more than terrify you to your core.

Hans Zimmer’s score for “Inception” can make life feel bright and sunny on a cloudy day. If the music from “Raiders of the Lost Ark” doesn’t make you feel awesome inside, you may need to visit your doctor. There are plenty of great film scores that leave an impression on your ears, your heart or your soul. When they do that, you know they’ve done their job. Here’s ten that I love.

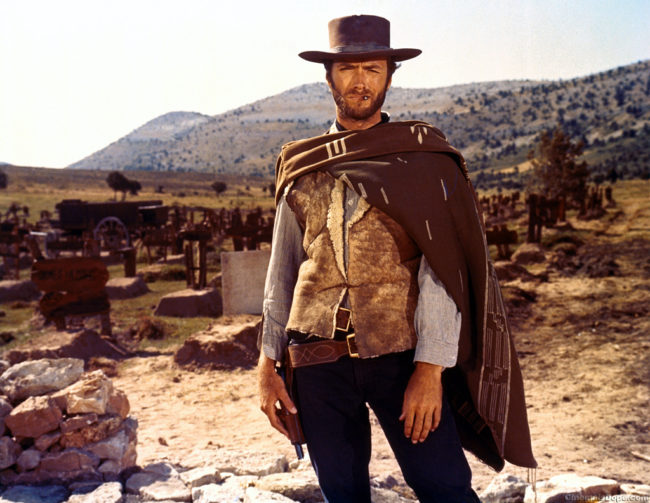

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), Ennio Morricone

“The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is one of the great dude movies of all-time. Call it Spaghetti Western if you like, and obsess over Sergio Leone’s genius direction. Marvel at the hyper close-ups of razor-stubbled faces with beads of sweat sticking in the filthy three-day growth on all the faces. Note the subdued acting of Clint Eastwood, the sweeping vistas and epic shootouts. While you’re doing that, notice the first thing you thought of when you read the title of the film was the whistling intro and theme music. Morricone has his audio footprints all over this picture. The robust sounds he comes up with are a perfect summary of the world this film inhabits: dusty, wind-swept deserts punctuated with piano and horns. If anyone ever managed to capture the sound of moral decay and betrayal, it was Morricone and it was this film score.

Vertigo (1958), Bernard Herrmann

With the lush discord of “Vertigo,” composer Bernard Hermann fused romantic and chilling sounds to make the visuals on screen even more effective. Alfred Hitchcock was a master filmmaker at the top of his game. Herrmann gave him spiraling music that flashed nightmares through your ears as you saw them tumble on screen.

Jaws (1975), John Williams

Back in 1975, the scariest thing to play in movie theaters was a cello. “Jaws” terrified audiences with a malfunctioning prop of a shark and a John Williams score. His strings build the drama and suspense and Steven Spielberg created the summer blockbuster event film. The emotional core of the film rode home on the shoulders of Williams’ epic score. The orchestra starts to play low and grows with intensity and loudness. The pace quickens and becomes deafening. As the dorsal fin appears in the water, the orchestra comes to a halt. It was then that you squirmed in your seat and knew what was transpiring on screen was worth paying attention to — you did not want to miss a thing.

On the Waterfront (1954), Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein composed only one film score, and it is one of the all-time greats. “On The Waterfront” had a brutal, street-level feel to the film and Bernstein’s percussive score brought out violent mood and gave an urban feel to the film. Bernstein did write for the stage musical “West Side Story,” which was adapted for the big screen, but the roughly 20 minutes of music he composed for “On The Waterfront” was his only contribution specifically for film. Such a pity, since his work here is beautiful, tense and filled with urgency.

The Godfather (1972), Nino Rota

There is something very Italian about Nino Rota’s score for “the Godfather.” You can almost smell the garlic frying and red wine being poured as the piano begins. There’s an inherent subtlety to Rota’s work, a majestic sweep followed by a solemn peace that comes across the screen. It’s the kind of music that feels like an immigrant in a strange land would make while trying to make sense of a new world, all while still longing for the one left behind. In the film’s most emotional scenes, it’s the music you’re not aware of that is adding weight to the words and the filmmaking.

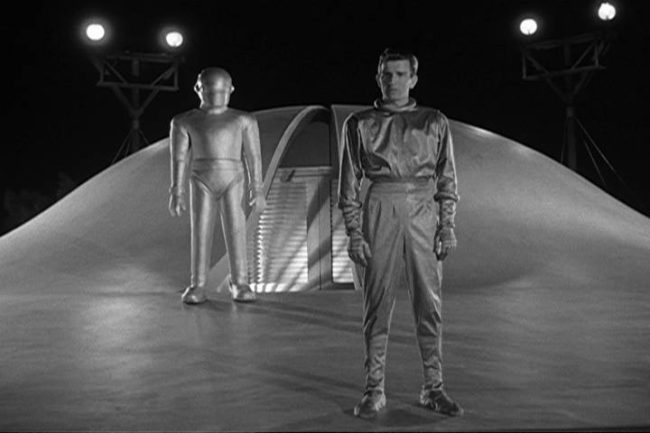

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Bernard Herrmann

Theremins, electric organs and tubas all fight for supremacy in a film score that sounds like outer space has landed on your front door. Bernard Herrmann’s first film score is also his best. “The Day the Earth Stood Still” was a sci-fi movie that was an allegory for the times it was released in; everyone was afraid of the new-comer, the foreigner and anyone that looked or thought differently. Richard Wise directed this film about first contact and how mankind would find new ways to screw it up with a subtle hand. The film is creepy and unsettling, the score matches it note for note, scene for scene. The theremin was not a widely used instrument, but Herrmann rode it to near-perfect use.

Chariots of Fire (1981), Vangelis

There are several times when the film score is more memorable and vivid than the movie it serves. ”Chariots of Fire” is a great film, a well-made film, but it would not be the same without Vangelis’ moving score. This is the film that took home the Best Picture Academy Award over “Reds” and “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” and it is hard to think it would have won without the help of some very powerful music swelling over the action onscreen. There is the epic sweep of Vangelis’ theme as the team of Olympic hopefuls run along the beach that stays with you for days after seeing the film.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Alex North

Alex North is credited by many as the first person to create a important jazz score for cinema. That is open for debate: One thing that is certain is North took Elia Kazan’s tense, heated battle of the sexes and infused it with jazz rhythms that perfectly suited the scenes they served. There’s a blurting two-note trumpet blast that kicks things off and a duel between saxophone and clarinet that defines Blanche DuBois and her broken spirit and faded dreams before she says a word.

Star Wars (1977), John Williams

Yes, John Williams again. As a kid seeing “Star Wars” for the first time and seeing the title crawl, hearing the sweeping, orchestral power of the main title sequence was a life-changing experience. Up to that point, I’m certain I was aware of film scores and music in films, but they seldom grabbed my attention and drew me into the film. Many composers have worked long and hard throughout their lives and never caught the zeitgeist the way Williams did in the opening minutes of Star Wars. He also introduced every kid my age in the theater to orchestral music and the power it has to bring out every emotion you can feel in the space of five minutes.

The Pink Panther (1963), Henry Mancini

If the question is “what is the slinkiest, coolest film score ever?” then the answer is Henry Mancini’s jazzy wonder that is “The Pink Panther.” Da dum, da dum… you know the rest. It’s a true work of art, combining piano and horns and a rare combination of intrigue and playfulness. Over his lengthy career, Mancini would win four Academy Awards and contribute to more than 200 films, but none as cool or hip or of the moment as this one.