Why do I love silent films? It’s both a simple and a complex question. The simple answer is that they’re movies and I pretty much love every genre you can think of and then a few more. More complicated is the fact that so many pioneering techniques, that are matters of fact now, were created by pioneers who were working without a net. The early work by the Lumiere Brothers is close to genius. They created projectors that allowed multiple people to see a film together. “Sortie de l’usine Lumière de Lyon” (1895) is considered to be the first actual film. Everything before was an experiment or proof of concept. Without the heavy lifting they did, along with Thomas Edison, Saturday matinees would never have happened. There is so much innocent joy in watching what must have been an incredible moment of discovery for the early directors, actors and writers. To see their ideas fleshed out and brought to life thrilled audiences around the world.

Advancements came fast and furious at the beginning of the twentieth century. Soon enough, there were viable films that told actual stories. That’s the part I enjoy most. Seeing the innovation of Georges Méliès’ “A Trip To The Moon” (1902) or Edwin S. Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery” (1902) is seeing narrative film, sci-fi and the western genres all be born. Too many times contemporary films come off as too market-tested and geared toward an audience. Silent films seem to have been made for the love of creativity. I have yet to get tired of unearthing some new old film I’ve never seen before. I would rather watch the Keystone Kops instead of “Bad Neighbors” any day of the week.

In 2016, plenty of it is available on Youtube or for download. There are also some fairly decent quality DVDs and Blu-ray versions of early works of art available for those interested. There’s also some that are nothing short of dreck. Just like every other era, the early days of film saw artists with vision crowded out by opportunists trying to make a quick buck. Fortunately, there is plenty of the good stuff that survives. Here’s a list of some of the silent films that shaped cinema, wowed audiences, or just provided me with an hour or two of escapist wonder.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

One rainy morning around three a.m., I wandered up the hall. I could not have been more than seven years old. My brother Joe was awake in the living room, and the screen flickered away on the t.v. What he was watching was “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” Even as a kid, I could tell that this was German Expressionist filmmaking at its twisted, surreal, finest. From the askew streets to the warped roofs and tilted staircases, this film tells the story of a mysterious doctor and the sleepwalker he uses as a murder weapon. A demented ride through a spooky cityscape. Someone once said watching this film is like watching yourself lose your mind. She was right.

Intolerance (1916)

D.W. Griffith had vision. Sometimes it was hideously racist and blunt, as in 1916’s “Birth of a Nation,” and sometimes it was sweeping and epic, like it was with 1916’s “Intolerance.” With a meticulous eye for detail, and the then-unheard of sum of $2 million of his own money, he recreates Babylon, and shows it off in elevator shots with its four stories from four different eras. The concept was ingenious, the stories weave in and out and it builds to a climax that is worth the investment. Lillian Gish would still be making movies in 1987, but here she was young and sultry, and clearly the biggest star in Hollywood. Griffith would lose money on “Intolerance,” but cement his place as one of the film industry’s giants.

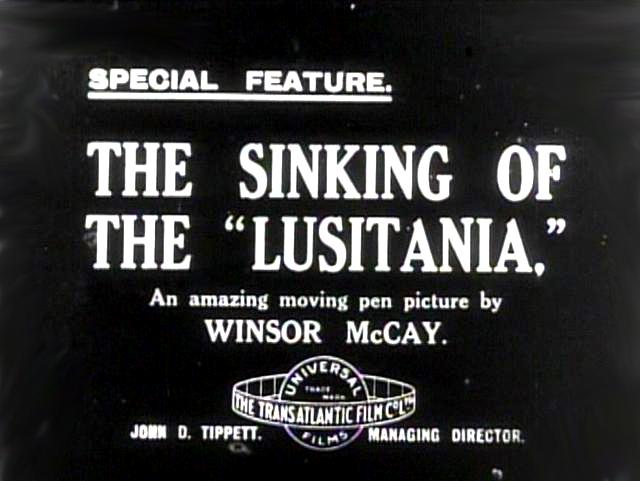

Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) / The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918)

Silent animation could be very hit or miss. Among the early hits were a pair of films by Winsor McKay. “Gertie the Dinosaur” was animation fused with live presentation. McKay was as much a showman and pioneer as he traveled the world showing off his creation: A huge, gentle, downright lovable dino named Gertie. He would stand on stage and order the adorable but seldom obedient dinosaur around. That showed McKay’s kinder side. He could pitch propaganda with the best of them though.

McKay created what may have been the first protest cartoon with a heart-wrenching animation short of the torpedoing and sinking of the Lusitania ocean liner off the coast of Ireland on its way from New York. The rippling water and curving cloud of smoke and the ocean liner itself is animation at its most gorgeous. The site of lifeboats spilling passengers into the ice-cold Atlantic and innocent people falling to their deaths are more disturbing than “Ghost in the Shell” would be decades later. It was pure propaganda, and it worked.

City Lights (1931)

Charlie Chaplin was a perfectionist, a womanizer and plenty of other things. One of those other things was a genius craftsman at bringing comedy and tenderness to places where they were not usually found. The plot is simple: The Tramp tries to help a poor, blind flower girl, played by the adorable Virginia Cherrill. Chaplin makes more than a movie, he makes a statement about what wealth truly is and makes you smile and laugh and cry on the trip. The rest of Hollywood had converted to sound and silent films were a dying breed by 1931, but Chaplin held out to create his favorite film.

A Page of Madness (1926)

Japanese director Teinosuke Kinugasa must have seen the German Expressionist films and thought, “Nice, but too subtle.” “A Page of Madness,” or sometimes titled “A Crazy Page” is about as dark an examination of the human psyche that was ever put to film. Kingusa explores the minds of those trapped in a mental institution and features a man working there as a janitor to free his captive wife. There are no title cards and the use of distorted lenses twists things into progressively intense moments of insanity. Since there were so few lights for the production, the sets were painted silver to help reflect more light onto the scenes. It also had the added effect of making shadows dance and an eerie glow emanates from behind everything. This film was lost for 50 years until it was discovered by the director in a shed in 1971. The budget was so tight, the actors and the director all pitched in to paint set and act as crew during the one month production.

The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

Jean Epstein’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” is otherworldly in the way it feels and plays out. The use of multiple exposures were fairly common in the silent era. Filmmakers were trying to invent new ways to tell a story and impart an idea to the audience. Epstein takes visual effects to new levels. The layers of fog add dread and menace to each shot. Edgar Allen Poe’s morbid tale is the source material, but it is more a launching pad and a template than a hard, fast, rule. Jean Debucourt is amazing to watch. Luis Buñuel was Assistant Director on the picture. He quit when he and Epstein clashed over the director’s decision to ignore most of Poe’s story.

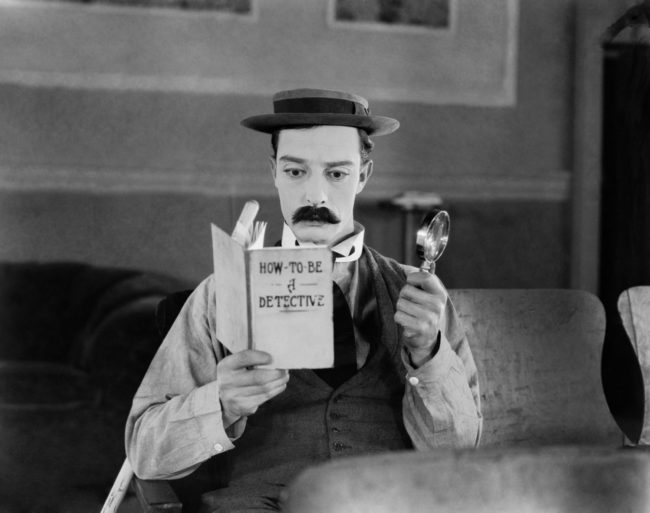

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

Buster Keaton was at his creative peak with “Sherlock Jr.” Comedy and fantasy meld together as Keaton plays a projectionist studying to be a detective. The film-versus-reality struggle weaves in and out so seamlessly, and the gags never stop. Ordinarily, silent comedies rely heavily on visual gags that are funny at most for two or three viewings. Nearly 100 years later, “Sherlock Jr.” still elicits laughs.

Safety Last (1923)

About the only thing you need to know about this film by Fred C. Newmeyer and Sam Taylor is it is hysterically funny at almost every turn. It is also the film with Harold Lloyd’s famous building-scaling sequence. There is also the scene with his famous clock-hanging finale. That alone makes this a film worth checking out.

Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror (1922)

While I can appreciate F.W. Murnau’s efforts to make a shadowy tale of vampires and the forces of evil, I can’t get past the fact that my wife and I laughed through the whole thing. Sure, it helped define the horror genre, gazing into the bleak, shadowy soul of Nosferatu, it just made us get a serious case of the giggles. Granted, it was 2:00 a.m. when we watched it for the first time, but it still made us chuckle the next day, after a full night’s sleep. That is not to say that it’s a bad film; In fact, it’s quite good at what it does. Since Murnau made Bram Stoker’s Dracula without permission, we get Max Schreck as Count Orlok, a despicable pointy-eared creature, large of stature, bald and pretty much the embodiment of terror. Great use of shadows and stark black and white contrasts.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

To put it simply, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali are just this side of batshit crazy. Every college kid sees this movie in film class and walks out of the surreal collection of strange images wondering what the hell they just saw. What makes “Un Chien Andalou” a masterpiece is Buñuel and Dali’s visual compass. Ignore the title cards, they’re nonsense. Get lost in the flow of what is in front of you and try not to get too queasy when the eyeball sequence happens. After seeing this in film class, my buddy Paul and I left campus and went to lunch. When the food arrived, he looked up and said, “I think that movie killed my appetite. Forever.” Dali would be proud. Buñuel would probably ask, “are you gonna eat that?”

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film is basically a revolutionary call for action. It’s also one of the best films about war/revolt ever made. Some versions of the film are slowed down, distorting the pace and making it seem sluggish. It’s worth finding a fully-restored copy. Set in 1905 and depicting that year’s revolution, Potemkin is a story of mutiny in Odessa harbor. After being served maggot-infested meat and enduring a captain that orders the execution of dissidents, all hell breaks loose. The revolutionary leader is killed and his body is taken ashore to lie in state. The townspeople race to the ship in fishing boats, bringing supplies to the sailors’ aid. The gathering on a breathtaking, crowded flight of steps overlooking the harbor is a site to behold. Pity it does not last long. The Cossacks arrived to restore order. What they get instead is a massacre of townsfolk running for their lives, trampling one another, falling dead from the hail of bullets, courtesy of row after row of czarist troops. The sequence on the Odessa steps is simply a ballet put to film if ballet were a bloody massacre. When a naval squadron is sent to retake the battleship, they let it pass by unharmed instead.

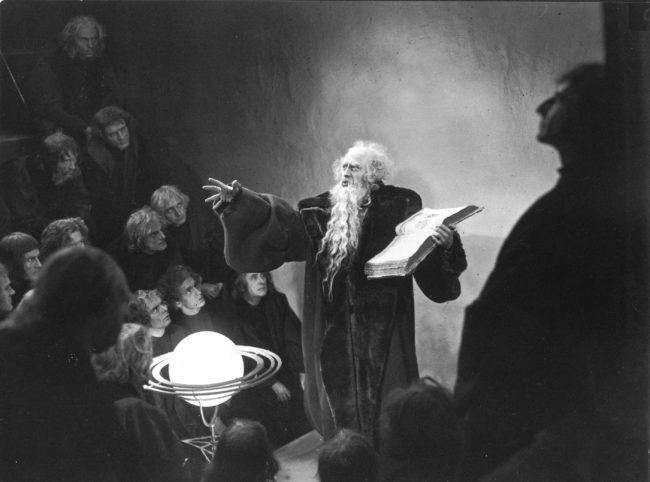

Faust (1926)

Before he headed to America, F.W. Murnau was one of Germany’s finest directors. Maybe the best. “Faust” is his final German film and a serious, stylish masterpiece. Special effects and camera trickery seem to be invented as you watch the cameras race through the fog and bring Hell into perfect view. Emil Jannings as Mephisto is all menace and evil. The lesson we learn? Don’t make a deal with the devil. Just don’t.

Rotaie (1929)

The title translates as “Rails,” as in riding the rails. And that is precisely what this movie is about. A young couple stays in constant motion and on the move in the industrial age. They get to live the good life and the not-so-good life as well as moments of joy followed by great uncertainty. Mario Camerini used the camera as a tool to help impart emotions and capture life at its best and most shallow. His films grew tamer, more conservative and more socially inline with the rise of Benito Mussolini. Some folks resorted to referring to him as a fascist stooge.

Pandora’s Box (1929)

Louise Brooks was a stunning beauty with an iconic hairstyle, a rare screen presence with acting abilities that were far beyond most Hollywood players in her era. She also seemed to rub plenty of people the wrong way with her outspoken nature and take no bull attitude. Her output of films in the U.S. is fairly limited. Where she made her mark was in Germany, working with director G.W. Pabst. As Lulu, Brooks gives a performance that sticks with you days after seeing the film. She is at times cheerful and childlike and then, just as easily, the tragic femme fatale. Pabst’s direction is easily decades ahead of its time. He is essentially leaving silent film tropes behind, even while still making a silent film. It is a fairly dark ride. The lighting is expressionistic, and the film leads to the recompense for a life of frivolity, gambling and wanton sex. Some historians have argued that Lulu was the first lesbian character portrayed on film. I have no idea if she is or not. All I know is that after seeing “Pandora’s Box,” I had to rewind it to watch it again. There are very few films that capture a director and an actor both at the top of their game. Pabst and Brooks made each other better. What they came up with together is more than a movie, it’s the Roaring Twenties as art and angst on film.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

Everyone even vaguely familiar with movies knows of at least one film that goes hideously over-budget and ends up a bloated mess that ruins careers. “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ” is pretty much Patient Zero. Out-of-control spending, a conga-line of directors, horror stories from the set and yet it ends up a gripping tale of epic drama. There’s a pirate raid and the now-famous chariot race that were the benchmark of creativity and cinematography for decades. In all, 42 cameras were used to film the chariot sequence, 48 for the pirate scene. That is a record that will probably stand for a lot longer. It took until 1931 for the movie to recoup its costs.

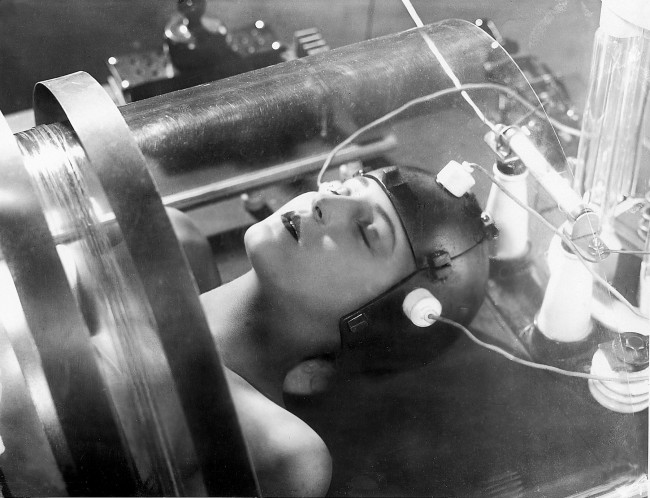

Metropolis (1927)

“Metropolis” is about a subtle as a sledgehammer to the head. It is also a constant flurry of iconic images and director Fritz Lang’s idea of what a future will look like. All sci-fi, religious overtones and massive bits of over-acting fuse together into a tale of the haves and the have-nots. Was Lang a visionary, or did he just get lucky and end up with a film that predicts a corporate-run state looking for a messiah? During the rooftop chases, the sweat-dripping henchmen, the tortured workers and claustrophobic catacombs that unveiled as I watched, I never quite figured out the answer to that question. All I know is that the night I saw it, the theater had the modern soundtrack with pumping bass and Freddie Mercury, Billy Squier, Adam Ant and Bonnie Tyler belting out the tunes. It must have seemed like a great idea at the time. The film can stand on its own.