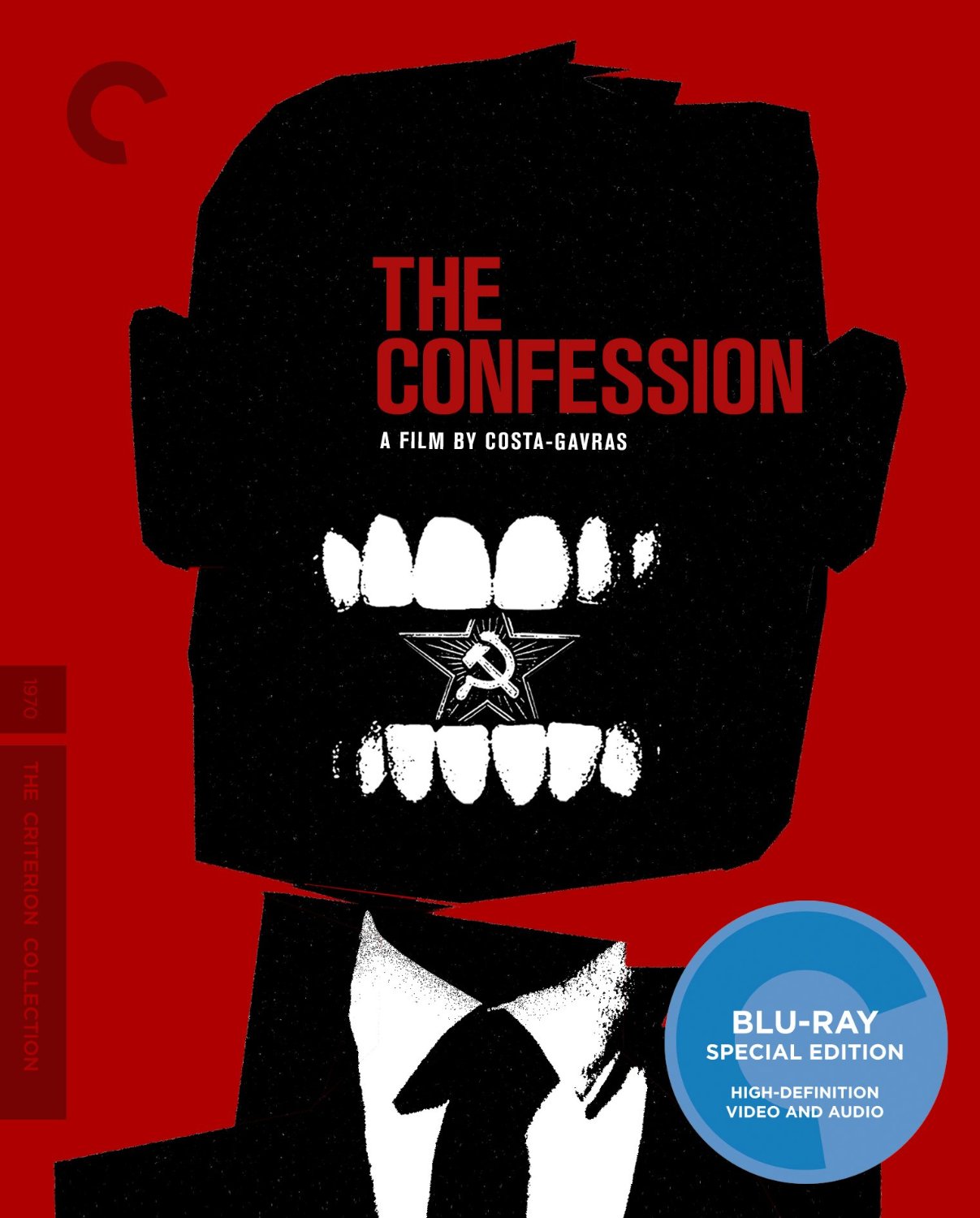

Another Costa-Gavras’ film, The Confession (1970), again braves the political landscape to tell the true story of Artur London. Based on the book that London and his wife had written, Costa-Gavras’ film dramatizes the Slánský trial – one that the author had participated in as a co-defendant among 13 other high-ranking officials of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia accused of being Trotskyites, Zionists, and Titoites; in other words, disloyal dissenters of the USSR who had supposedly conspired to overtake the country. In the film, Artur is kidnapped and then tortured until he authorizes the official narrative his captors have invented to suit their political ends with a signature.

I’m finding that the subjects Gavras explores have an immediate appeal to me. Of no credit to Gavras and his team beyond simply choosing to make a film about London, his story is inherently interesting; London was an actor—in some capacity—in the Spanish civil war; a Jew and a communist, he had spent time in occupied France which lead to his internment in a concentration camp (where, according to the film, one of his children was born); and he endured an undeserving fate as a political pawn of the Soviet Union to indict the West.

I’m finding that the subjects Gavras explores have an immediate appeal to me. Of no credit to Gavras and his team beyond simply choosing to make a film about London, his story is inherently interesting; London was an actor—in some capacity—in the Spanish civil war; a Jew and a communist, he had spent time in occupied France which lead to his internment in a concentration camp (where, according to the film, one of his children was born); and he endured an undeserving fate as a political pawn of the Soviet Union to indict the West.

Gavras does this story absolute justice (if only London’s comrades had done the same for him). The suspense is enough to keep one entertained. Hitchcock has long carried the title of “Master of Suspense” — and he is — but Hitchcock created suspense out of tedious, ordinary acts. Take for instance Marnie, where our titular heroine had to slip past a janitor unnoticed by tip-toeing her way out of the room they occupied, heels in hand, or in The Birds when a group of children have to flee from their school and pass a murderous murder of crows perched on, if memory does no disservice, a jungle gym. It is in the simple act of walking that Hitchcock conjures the suspense in his audience. Gavras is able to create suspense in abstractions, especially in the psychological rendering of his characters; the conflict of London to stand in solidarity with the truth, with safe assurance this will lead to his execution, or to appease his captors so that he can return home to his family; the absolute silence—not even a hint of white noise—that occurs right before the trial takes place; and the irony in a scene wonderfully executed through the juggling of close-ups and wide shots that shift from him being tortured to, at an earlier time, him administering similar treatment. The turning of, literally, a table as Artur now finds himself on the other end of it.

From State of Siege – technically a later release (I just happened to get my hands on it sooner) – the table is also turned to examine the Eastern political apparatus. Between these two films, he sets a precedence of attacking political systems rather than ideologies in themselves—although there is some inseparable overlap, the emphasis is on the former. This movie was criticized for being anti-communist, but too many factors seem contrary to this view. Superficially, Gavras worked with the Londons and another communist proponent on this project—likely as, partly, a stamp of approval on the latter. Analysis of the film further suggests this. The protagonist, Artur, asserts his “faith” in communism at the resolution of this film even despite the betrayal he experienced. Gavras is condemning Stalinism; the unquestioning loyalty demanded by “The Party.” This film is not anti-communist. It’s anti-totalitarianism. It’s anti-politics-driven-by-compulsion. It’s anti-unquestioned-commitment to a political agenda or entity.

From State of Siege – technically a later release (I just happened to get my hands on it sooner) – the table is also turned to examine the Eastern political apparatus. Between these two films, he sets a precedence of attacking political systems rather than ideologies in themselves—although there is some inseparable overlap, the emphasis is on the former. This movie was criticized for being anti-communist, but too many factors seem contrary to this view. Superficially, Gavras worked with the Londons and another communist proponent on this project—likely as, partly, a stamp of approval on the latter. Analysis of the film further suggests this. The protagonist, Artur, asserts his “faith” in communism at the resolution of this film even despite the betrayal he experienced. Gavras is condemning Stalinism; the unquestioning loyalty demanded by “The Party.” This film is not anti-communist. It’s anti-totalitarianism. It’s anti-politics-driven-by-compulsion. It’s anti-unquestioned-commitment to a political agenda or entity.

Over four decades old, would one be hard-pressed to find commonalities in contemporary politics? Is commitment to a party ever valued over reason? Certainly not. Democrats are just too idealistic in their policies. Republicans are just too indifferent to the poor and the working class. There is absolutely no compromise to be made and a gridlocked, stationary, immovable political process is certainly the best option. And it’s the 21st century. Totalitarianism is a relic of the past that only exists in North Korea. It’s not like the United States has ever tried to collect phone and email records of its citizens. If it did, I’m sure it’d be to protect its citizens against terrorism—certainly, if it did, the monumental successes would substantiate the merits of such a program. And anyways, can you really fault a government for surveilling its citizens when I look this good in my thriftily purchased argyle sweaters? Some admiring government official is probably drooling over my dick pics, argyle sweater and all, right now.

Speaking of something good to look at, this film also uses some interesting techniques that made it a pleasure to view. It’s rife with actualities that add to the film’s authenticity. The camera is almost never static, quickly changing its vantage point to guide the narrative. It does, however, pause in a few still-frames for dramatic emphasis. This happens, that I remember, once when the camera fixes itself on a character as London describes him and again, towards the end, on our protagonist’s eyes to impress upon the viewer how affected he is after coming home to his now-war-torn country. It does not take an amateur film critic, as nothing ever does (except perhaps to peeve editors Rob Patrick and Tom Bevis with chronically late articles), to appreciate how meticulous Gavras is with the camera.

Speaking of something good to look at, this film also uses some interesting techniques that made it a pleasure to view. It’s rife with actualities that add to the film’s authenticity. The camera is almost never static, quickly changing its vantage point to guide the narrative. It does, however, pause in a few still-frames for dramatic emphasis. This happens, that I remember, once when the camera fixes itself on a character as London describes him and again, towards the end, on our protagonist’s eyes to impress upon the viewer how affected he is after coming home to his now-war-torn country. It does not take an amateur film critic, as nothing ever does (except perhaps to peeve editors Rob Patrick and Tom Bevis with chronically late articles), to appreciate how meticulous Gavras is with the camera.

This film can feel looming with its length stretching longer than 2 hours. It shifts its attention enough to keep it from getting stale and has just enough memorable and brilliant scenes to forgive it when it gets tedious, recognizing those moments as necessary—or maybe a little drawn out—plot development. The final scene is powerfully poignant. The depiction of torture and how it is justified is deeply realistic. While bouts of boredom can seem like the real torture, a dedicated viewer will not walk away without recompense.

While The Criterion Collection seems to imply with its catalog that a film is rarely entertaining and great, sometimes that’s okay. At its best, The Criterion Collection offers films that let emotional and intellectual payouts, or even aesthetics and style, supersede mere base amusement. At its worst, you paid out thirty-plus-some-odd-dollars to be pretentious in pretending to like some movie you think is great because they told you so (I’m probably guilty of this, but mostly because I’m too cheap to not delude myself into thinking my purchases are always well spent). The Confession is definitely of the best Criterion has to offer. You won’t regret buying this one, at least not as much as I regret allowing loneliness, inebriation, and a camera phone to influence my decisions.