Comic Collectibility and the Forging of a Comic Nerd

Back in 1994 or 1995 — I’m getting old, I can’t quite remember these things as well as I used to — my mom dated a guy who opened up a comic book shop. The memory is a little surreal this far away, but I remember those early meetings before the shop opened. My mom’s boyfriend, who we’ll call Pat, would sit in the dining room with two or three other guys shooting off ideas. Pat drew a cartoon dragon or something, I think, for a logo. After tossing around a few ideas for names, they turned to my brother and asked him what he thought they should name the store. My brother shrugged and said “the comic shop.”

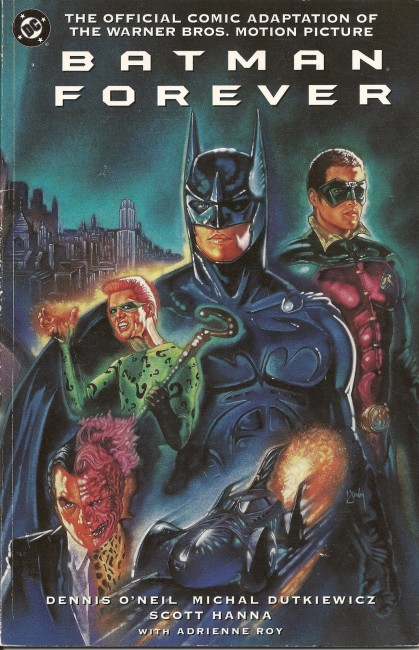

Long story short: the other three dudes would go on to open their own store called Comic Book Paradise using that cartoon dragon as their logo. As for Pat’s store: my brother’s suggestion stuck and The Comic Shop was born. Some of my best memories from being a kid were in that store: playing SNES in the back room, bagging-and-boarding individual issues (“remember,” Pat would tell me, “the shiny side of the board goes on the outside.”), thoroughly examining each and every book that entered and left that store. Occasionally, I’ll find small relics from that past, like one of the t-shirts Pat had made (which I later gave to Pat as a small memento) or photos of the Batmobile he rented for special occasions, parked there in front of the store. In fact, early in my friendship with Cinema Spartan’s own Editor-in-Chief Rob Patrick, he lent me the privilege of flipping through his comic collection and tucked in the back of a Batman Forever tie-in was a flier from The Comic Shop, promising a 15% discount if you brought in your Batman Forever ticket stub.

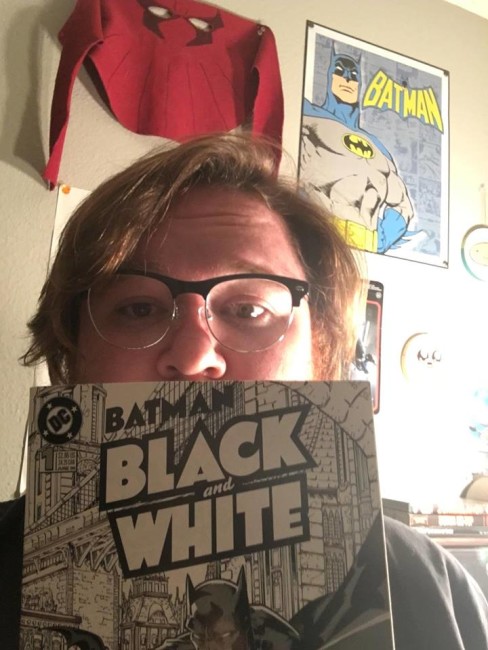

Now, all these years later, after thousands of dollars spent and hundreds of comics owned, dozens of Comic-Cons and handfuls of creator meet-and-greets, I can still remember the first comic book I ever read (Spawn #1, 1992, although I’m guessing I didn’t read it until 1994) and I remember the first comic I ever bought with my own money (Batman Black and White #1, 1996). Even though The Comic Shop shuttered its doors too early and Comic Book Paradise somehow outlived it by over a decade until the city claimed the land it stood on to build a new police department, I still remember that place. And although being so close to that store gave me all the resources I needed to be a life-long comic book fan (as well as a secret desire to someday open my own comic store), there’s an even smaller seed planted even deeper in my brain that I feel owns more of the responsibility.

Even before The Comic Shop, when I was maybe five years old or so, my dad called me toward a closet. “Look at this,” he said, and from the top shelf, he pulled down a comic book. It was kept in a heavy-duty plastic case, the kind you see people putting early copies of Superman into. The comic inside, though, was one called Rubber Band Man. I had never seen or even heard of it before and I’ve never seen it since, but from that moment I was transfixed. I begged him to let me read it, and he resisted every plea. “The oil on your hands will mess up the ink,” he told me.

For those of you too young to remember, back in those days comics were printed on newsprint with the same kind of ink newspapers used. “We’ll have to get special gloves before we can open it,” he said with a calm assurance that someday he’ll pass the comic down to me. Every time I saw him after that, I’d ask to read it, and every time the answer was the same. I can’t write into words the kind of profound, prodigious anger I felt every time he rejected my request, the kind of irrational and bad-tempered rage only children and Donald Trump are prone to.

I made a vow then and there, in that childhood-induced lunacy of acrimony, to read every comic book ever created. Twenty-three years later, that’s been my only New Year’s resolution. I visit local comic shops twice a week and have to swim through a stack of issues to get to my armchair. I’m a long way off from reading every comic ever, but I feel like I’m making some good headway. Every comic book I’ve ever read has been out of spite, and all this way, I’m haunted by this notion of comic book collectibility. I’ve been trying to round out my Empire: Uprising issues, but issue three has managed to evade me. I finally found a copy and, to my horror, found that it had been marked up to fifteen dollars. The reason? It was a variant cover.

I’ve never been able to find the comic Rubber Band Man, but here’s the Spinners’ album of the same name.

Comic books surged in popularity in the 1930’s thanks to an obsession over superheroes fostered by a young audience that felt disenfranchised and rejected by the society they found themselves a part of. Truly an outsider medium, this notion has continued to persist in the comic book culture without any sense of comic collectibility. But for fifty years, comics failed to earn any kind of legitimacy. Something interesting happened in the 1980’s, though. Starting in the late 1960’s, comic readers began organizing comic conventions. Those early conventions didn’t resemble the behemoth Comic-Con and other conventions have become. Instead, it more resembled a handful of dudes getting together in a room where they actually talked about comics.

Not long after those conventions started to become increasingly common, more enterprising fans took it a step further and began opening specialized shops to sell comics and related merchandise. By the time the 1980’s rolled around, comic culture was hitting full swing, and damned if the Big Two didn’t notice. By this time, the classic comics from that first decade had become old and mythic enough to become massive collectors items, and the fantasy of coming across one of those iconic titles fueled the mass exodus these stores were witnessing. This opened the era of comic collectibility that would dominate the late 1980’s and early 1990’s.

Of course, Marvel and DC loved the idea of people buying more comics — people buying, say, two or three copies of each issue: one to read and a few others to keep sealed up with delusions that someday it’ll boast a big price tag at auction — and they wanted to speed up the process. That’s where this notion of forced comic collectibility comes into play. All of the sudden the typical roster of new issues were supplemented by a host of exploitive extras: variant covers, sealed-in trading cards, holofoil graphics, sealed specials and more. It was the Big Two’s hope that these stunts would send sales rocketing through the roof.

For the most part, it worked. I know people who still have sealed copies of The Deaths of Superman, Spider-Man, Captain America, and more. Others hoard first issues as if they were gold coins. The 1980’s sold more comic books than any other decade in history, overshadowed only by our current decade where Marvel movies pack cineplexes every six months and every comic from the Big Two are somehow connected in huge overarching storylines. All of these tactics were designed specifically to force comic collectibility by the publishers, resulting ideally in increased sales.

None of this is to say that collecting comics is inherently bad. Like I said, I remember the first comic I’ve ever read and I still own the first comic I ever bought. Some people like The Amazing Spider-Man #129 because it was the first appearance of The Punisher, who happens to be their favorite character. Others probably like Fables #5 because it was the last comic they bought before they lost their virginity. But the last reason you should ever collect a comic is because Marvel or DC told you to. It’s almost as if these people have forgotten what comic books were created for: to be read. I can’t help but think, all these years later, that this idea of comic collectibility is what was in my dad’s head when he wouldn’t let me read that issue of Rubber Band Man he stashed on the top shelf of his closet.

By the end of it, I never got to read that copy of Rubber Band Man, and it was never given to me as was promised. Soon, though, it didn’t matter because once The Comic Shop became a reality, what good was one measly comic when I was surrounded by every comic ever? Still, the lesson I learned from both The Comic Shop and from Rubber Band Man was that the best use for comics wasn’t hiding them in your closet, but to be read. Comic collectibility dosn’t mean anything. And that’s the reason why I buy comics for my nephews and niece, and when I do, I let them keep them. Sure, sometimes I’ll see one with the cover yanked off and sometimes they’ll wind up on the floor, but at least before they meet those fates, those books were able to achieve their purpose.