Film Noir. The term was coined in 1946 by French critic Nino Frank. He saw a mood change in the films coming out of the Post-War American cinema. Something darker, a trend of detectives, dangerous women and pot-boiler plots ripped from the pages of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and James M. Cain pulp

novels. Their words were coupled with international directors like Fritz Lang and Michael Curtiz who fled war-torn Europe for greener, less battle-scarred, terrain in Hollywood.

Usually set in the naked city, noir could also be rural on occasion. Mostly, it is identifiable by the heavily-stylized product on screen; hyper-exaggerated camera angles, flashbacks and shadows, lots and lots of shadows. There is also a healthy dose of German Expressionism, neo-realism, and throw backs to the gritty heist films of the 1930s. Throw in bits of Gothic theater and a decent slab of B-movie/documentary feel and you have a genre. The aforementioned badass women usually ended up hiring, and eventually betraying, the anti-hero. He was most always a gumshoe, a private eye, or a term that is so odd in today’s slang it seems insulting, a dick. The heyday of film noir was most likely 1940-58, but there are still moments on the screen that the genre peaks through.

Below is a dozen films that feature the misfits, the derelicts, the unwanted, unwashed and unethical. In other words, welcome to the seedy underbelly of humanity.

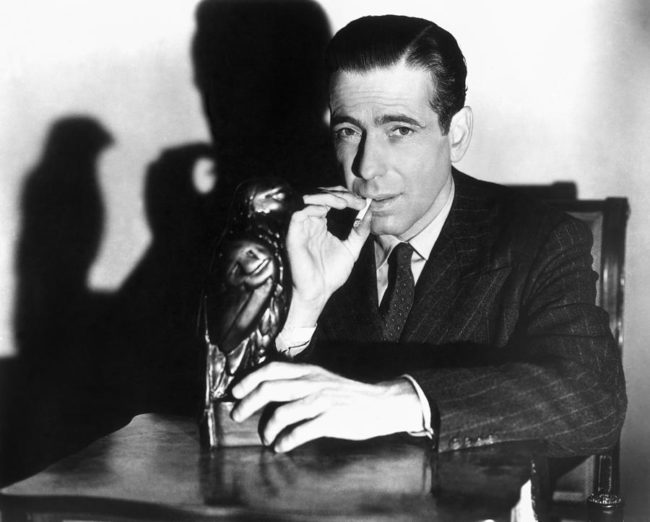

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

There had been movies that could be classified as film noir, but this was the first time the world noticed. Some argue that the obscure, watchable, “Stranger on the Third Floor” (1940) came first and was the first true film noir. Well, okay, it came first. But with “The Maltese Falcon,” John Huston knocked it out of the park. It’s a classic film, with an archetypal detective, Humphrey Bogart’s note-perfect Sam Spade. Dashiell Hammett’s novel was fertile ground setting the stage of what seems to be plot concerning a murder mystery. There is also the titular MacGuffin,

the black bird, the stuff of dreams. Bogart almost creates the anti hero in this role. He fills the screen with detached cool and seeing him kissing his dead partner’s widow while the body’s still warm only helps cement his likability. He may be nobody’s sap, but he is a sucker for an attractive woman with a dark secret. And the woman he meets, Mary Astor, is indeed attractive and has a secret dark enough to be considered onyx. There was a previous attempt at “The Maltese Falcon” in 1931. While it is a solid movie, it is not the classic version. Plus when you throw in Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, you’re assured on a good time.

Double Indemnity (1944)

The name Fred MacMurray conjures up images the kindly, all-knowing dad in “My Three Sons” and Barbara Stanwyck as the bitter, aging matriarch in “The Thorn Birds.” For me, the pair could not be more different than the characters they’d play later in life. In 1944, under the direction of Billy Wilder, the pair were amazing. Amazing in a deplorable way. MacMurray uses his everyday unassuming nice guy persona to mask the unlikeable, hard-edged Walter Neff hiding barely beneath the surface. And he falls for Stanwyck’s temptress with a soul blacker than Turkish coffee who happens to be married. Her marriage is a problem she’s convinced Neff can help her out with by killing her husband. The backdrop is mid-century Los Angeles, a city growing faster than it can keep up with and more modern than the tired east coast. Wilder spins a tale of unrepentant bad people.

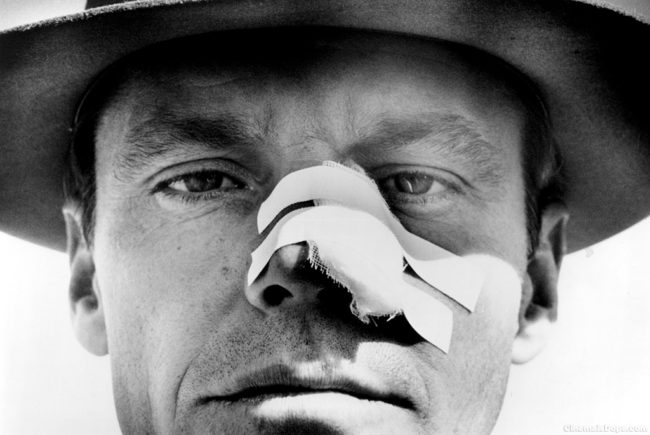

Chinatown (1974)

Roman Polanski’s crime classic is nothing short of amazing. Polanski does have the benefit of Jack Nicholson at the height of his acting power and a great story of a power struggle over water rights in Los Angeles in the 1930s. There is an ominous feeling going on underneath the plot as every character has a secret to hide and is willing to go to great lengths to keep those secrets secret. Nominated for 11 Academy Awards, “Chinatown” won the Oscar for Robert Towne’s original screenplay. There is also the added benefit of an aging John Huston and a young Faye Dunaway working their asses off to deliver on a great script. The pay-off for Nicholson’s J.J. Gittes is when he uncovers the truth. He regrets every minute of knowing what he can never un-learn.

Night and the City (1950)

![Naked City, The (1948) | Pers: Ted De Corsia | Dir: Jules Dassin | Ref: NAK004AR | Photo Credit: [ The Kobal Collection / Universal ] | Editorial use only related to cinema, television and personalities. Not for cover use, advertising or fictional works without specific prior agreement](https://www.cinemaspartan.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/NAK004AR_640x391.jpg)

London is the backdrop of “Night and the City,” director Jules Dassin’s nightmarish portrait of greed. Blacklisted for his Communist sympathies, 20th Century Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck Shipped Dassin off to England to shoot the screen version of Gerald Kersh’s best-selling novel. According to legend, lead actress Gene Tierney was allegedly suicidal over her recent break-up. “Night and the City” shines in large part due to Richard Widmark’s performance as Harry Fabian, a sleazy huckster in over his head attempting to infiltrate the local wrestling subculture. There’s a seething anger between Tierney and Widmark that boils over in her disappointment.

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Billy Wilder struck gold when he made “Sunset Boulevard.” It’s a raw, cynical, critique of postwar Hollywood. The film opens with the narrator floating in his killer’s pool. Dead. Gloria Swanson is epic as Nora Desmond, the faded beauty of a by-gone day. She was the queen of the silent era, but now she’s old, sad and busies herself manipulating an aspiring screenwriter, Joe Gillis (William Holden, nailing his performance). Desmond wants Gillis for something other than his pen. Jack Webb is included, perfecting his deadpan the he would take to the bank with “Dragnet.”

Erich von Stroheim portrays Desmond’s former director, also her first husband who is now her butler Max. He directed her in 1929’s “Queen Kelly,” well he did until she fired him. As she makes her dramatic descent down the staircase, ready for her close up, it’s the other faces you notice.

The Wrong Man (1956)

The master of suspense is at the top of his game here. Alfred Hitchcock fuses melodrama and realism into a noir classic. It’s the story of a man falsely convicted for robberies he never committed and the claustrophobic camera work only adds to the tension. Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda, nothing short of brilliant) is the bassist, Catholic, husband and father who is barely making ends meet, playing in a jazz combo at the Stork Club. He’s also the unlucky title character who pays the price for someone else’s crimes. The effect on his family is rough too, to say the least.

Blue Velvet (1986)

David Lynch is one messed up little dude. He’s also more talented than most directors currently working in Hollywood. “Blue Velvet” is a noir-ish mash-up of everything good and horrific in film. Kyle MacLachlan is the innocent man caught up in a world he never knew existed, Isabella Rossellini is is dark and troubled. There is also Dennis Hopper huffing helium, or god knows what, and an abiding sadness. There’s also no way to listen to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” the same way after seeing this film.

The Big Heat (1953)

By the time he made “The Big Heat,” Fritz Lang was already a legendary filmmaker. This film cemented his legend. Start with Glenn Ford as Det. Sgt. Dave Bannion, a pillar of moral certainty in the vague world of noir. Bannion is out to clean up the city after one of his colleagues commits suicide. Pretty much everyone but Bannion is on the payroll of the local mobster in charge. It turns into an almost holy crusade of righteous indignation and watching Ford devolve from dedicated family man with principles into a vigilante with laser-focus is unnerving. A sort

of precursor to The Punisher of comic book fame. Throw in Gloria Grahame as the moll and Lee Marvin as the second thug in charge and you have a winning formula. Corruption gets weeded out and the pile of bodies gets high. But the suspense and vengeance churns ever-forward, destroying everything in its path to justice.

Blade Runner (1982)

The genius of Ridley Scott was evident on screen. There’s a detective named Deckard (Harrison Ford), who roams the streets, hunting down replicants who have escaped grueling slavery out on the colonies and made it back to Earth. There’s the awesome Raymond Chandler voiceover, that gives the film a noir-esque feel. There are plenty of film noir aesthetics mixed into the dystopia — shadow-filled, rainy metropolitan exteriors, a brooding anti-hero, 1940s outfits and plenty of other flourishes. Then there is Rutger Hauer’s android Roy Batty. Batty, a replicant with

human appeal and an urge to live. There’s also the near-flawless third act, and Hauer’s amazing speech about “tears in rain.” Human or replicant, we’re all beings and we all have a limited amount of time on this planet. “Blade Runner” is not just great noir/sci-fi, it’s a great film.

The Third Man (1949)

There may be better written films. There may be better looking films. But there are few films more immediately engaging than Carol Reed’s phenomenal “The Third Man.” Vienna is a beautiful city. Reed captures and expands that beauty and keeps it off kilter with the help of expressionist camerawork from Robert Krasker. It’s a gorgeous set up for Holly Martin (Joseph Cotton at his finest), a man who writes Westerns. He arrives after being told of a job by his friend Harry Lime, who was tragically killed in an auto accident just prior to Holly’s landing. Things don’t seem

to add up and the details get shadier the deeper you look. Orson Welles pulls out all the stops and the foot chase is amazing.

Drunken Angel (1948)

Akira Kurosawa could make a movie in any genre and end up with a film that is superior to most everything that came before. With “Drunken Angel” Kurosawa uses the tropes of noir and takes the wind of of the usual macho sails. Tough guys turn into sniveling cowards in his hands and it is all part of design. There is a classic showdown, pitting Toshiro Mifune’s Matsunaga and Reizaburô Yamamoto’s Okada that makes the film worth watching by itself. Some critics say Kurosawa was thumbing his nose at the post-World War II U.S. Occupation Forces. If that’s the case, I missed the reference. But I still loved the movie and the way it never gets dull.

Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

By the time France got a decade removed from World War II, a sense of normalcy had returned to their daily lives. Cafes were open, music and art were abundant. Movies houses sprung back to life. Newspapers had space to fill, and they filled it with plenty of film critics. Many members of France’s New Wave genre got their start as film critics. In fact, it was through their voluminous writings and over-caffeinated discussions that the term “film noir” was first used to describe the glut brooding postwar films. Enter Louis Malle, not officially a member of the New Wave, he made his presence felt in France and the world. With “Elevator to the Gallows,” Malle paid homage to film noir and let loose Jeanne Moreau and Maurice Ronet on screen. The pair are hapless criminals with a plan to kill Moreau’s husband that quickly goes pear shaped when Ronet’s character gets stuck in an elevator. The editing is strange, and there is a musical score performed by MIles Davis. Definitely a quirky film, but one that pays dividends for sticking it out until the end.